4.2. HTTP#

So far, the HTML files we’ve created are just sitting on the computer we made them on. If you wanted to share them with someone, you’d have to send them a copy, like emailing the file or putting it on a USB drive. But that means your HTML files are kind of stuck on their own, unable to connect with anything else.

To solve this problem, the HTTP protocol was invented. It allows computers to share HTML files over a network, like the internet. Thanks to HTTP, your files aren’t trapped — they can be shared across the web, and hyperlinks can connect pages from anywhere in the world. This combination of HTML, hyperlinks, and the internet is what we call the “World Wide Web.”

4.2.1. HTTP Protocol Overview#

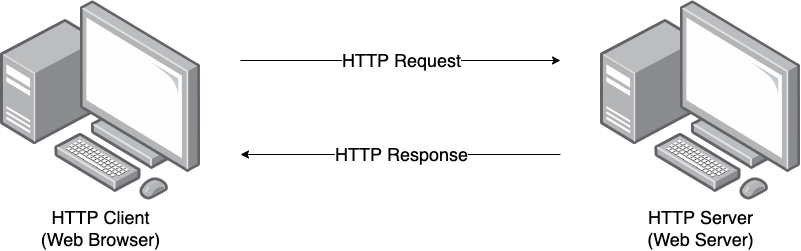

The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) defines a client-server protocol for the transmission of HTML (and associated) files over standard internet technology.

The term client is interchangeably used to mean the user’s physical device and web browser. While the term server is interchangeably used to refer to the software which processes the requests then returns appropriate responses and the physical device on which the software is running.

HTTP uses a “request and response” model. Clients send requests for a particular resource and the server provides the resource in the body of the response message.

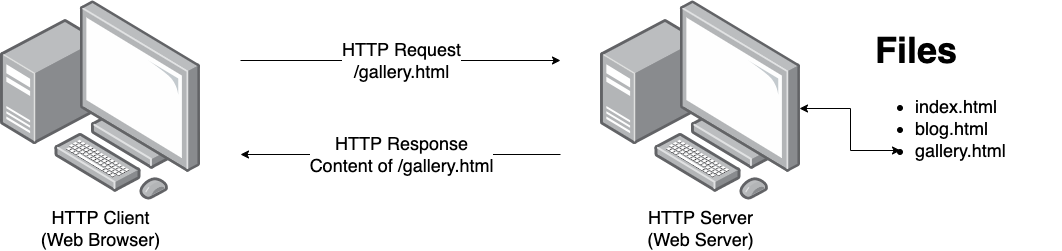

A client requesting a resource from a server.#

In general data is exchanged over HTTP in the following steps:

server starts and waits for a new TCP connection

client establishes a TCP connection with the server

client sends a request conforming to HTTP protocol over TCP

server processes request

server sends a response conforming to HTTP protocol over TCP

client and server close the TCP connection

The simplest web server hosts static content meaning that it reads the requested HTML files and returns them as the response.

A crucial aspect of the HTTP protocol is that it is stateless, meaning that each request is independent of the others and the requests cannot reference any previous requests. However we will see later, that we can add state to our web sites through shared information between client and server inside the request data.

4.2.2. HTTP Requests and Responses#

Request and response messages are sent as plain text but follow a very specific format.

Requests#

Let’s start with an example HTTP request. For example, requesting the Google homepage in your browser would send the following request:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: www.google.com.au

Let’s look at each line:

The request line

GET / HTTP/1.1consists ofThe host line

Host: www.google.com.au, which is a request header field that specifies the domain name the client is requesting the resource from. This is required since a single server may host many websites!

Request Specification#

METHOD PATH VERSION

Host: DOMAIN_NAME

Header-field-1: value1

Header-field-2: value2

...

Header-field-N: valueN

Breakdown:

METHOD, typically one of:GET- request that the server returns the specified resourcePOST- send data

PATH- path on the server to a resourceVERSION- normallyHTTP/1.1Mandatory

Hostheader fieldOptional header fields and values, e.g.

Accept: text/htmlAccept-Language: en

Response#

Continuing the example from earlier, the Google web server would respond with:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Monday, 8 Sep 2024 09:00:00 GMT

Content-Type: text/html

<!DOCTYPE html><html><head>...

where we have truncated the HTML to save page space.

Let’s look at each line:

The status line

HTTP/1.1 200 OKconsists of:the version

HTTP/1.1the status code of

200meaning the request was successfulthe status code reason phrase

OK

Date response header field

Content-type response header field

The body of the response, which contains the HTML of the page

Response Specification#

VERSION STATUS_CODE REASON_PHRASE

Header-field-1: value1

Header-field-2: value2

...

Header-field-N: valueN

BODY

Breakdown:

VERSION- normallyHTTP/1.1STATUS_CODE REASON_PHRASE- indicates the status of the request, typically one of:200 OK404 NOT FOUND500 INTERNAL SERVER ERROR

Optional header fields and values, e.g.

Content-Type: text/html

Status Codes#

A status code is a three digit number returned by the server to indicate the result of a request. Status codes are defined as part of the HTTP specification.

The codes are grouped into five classes and ranges:

Informational (

100-199)Success (

200-299)Redirection (

300-399)Client error (

400-499)Server error (

500-599)

1xx - Informational#

1xx codes are provisional responses indicating the server has received the request headers and is providing interim status while it continues processing. The connection remains open and the server will normally send a final response (2xx/3xx/4xx/5xx).

These informational codes can also be used to switch protocols.

Examples:

100 Continue— Server says “go ahead”, commonly used when a client wants to send a large body and checks first via settingExpect: 100-continuein the request header.101 Switching Protocols— Server agrees to change the connection, commonly from HTTP to WebSocket protocol after a HTTP upgrade handshake.

2xx - Success#

2xx codes indicate that the request was successfully received,

understood, and accepted. The exact meaning depends on the method: for example,

a GET typically returns the requested representation, while a POST may

create or trigger processing of a resource.

Examples:

200 OK— Standard success response. The response body usually contains the requested resource (forGET) or the result of the operation.201 Created— A new resource was created, commonly in response to aPOST. Often includes a Location header pointing to the new resource.

3xx - Redirection#

3xx codes indicate that the client must take additional action to

complete the request. Most commonly, this means the client should make a new

request to a different URL provided via the Location header.

Some 3xx codes are used for caching and conditional requests (notably

304), where the client can reuse a cached representation instead of

downloading it again.

Examples:

301 Moved Permanently— The resource has a new permanent URL. Clients and caches may remember the new location.304 Not Modified— The resource has not changed and the client should use its cached copy.307 Temporary Redirect— Temporary redirect where the client should repeat the request to the new URL.

4xx - Client Error#

4xx codes indicate that the request cannot be fulfilled due to a fault with the request from the client e.g. bad syntax, invalid data, missing authentication, insufficient permissions.

Examples

400 Bad Request— The server cannot process the request due to malformed syntax or invalid input.401 Unauthorized— Authentication is required or the provided credentials are invalid.403 Forbidden— The server understood the request but refuses to authorise it.404 Not Found— The requested resource does not exist or the server is not willing to confirm it exists.

5xx - Server Error#

4xx codes indicate that the server failed to fulfill an otherwise valid request due to an error on the server side. These often represent temporary failures, so retrying later may succeed (especially for 502, 503, and 504), though repeated failures typically require server-side investigation.

Examples

500 Internal Server Error— A generic server-side failure.502 Bad Gateway— A gateway or proxy received an invalid response from an upstream server.503 Service Unavailable— The server is temporarily unable to handle the request e.g. overload or maintenance.

Note

You can find a complete list and description of status codes here https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Reference/Status

4.2.3. Glossary#

- Client#

A client is the device (like your computer or phone) that requests information from a server, such as when you use a web browser to load a website.

- Method#

An HTTP method is the action that the client wants to perform, such as

GETto request data orPOSTto send data to the server.- Plain text#

Plain text refers to data that is not encrypted or formatted, such as regular text that can be easily read by both humans and machines.

- Server#

A server is a powerful computer that stores and delivers content (like web pages) to clients when they request it.

- Stateless#

In HTTP, stateless means that each request from a client to a server is independent, and the server does not remember previous interactions with the client.

- Static#

Static refers to web content that does not change or interact with the user, like a simple HTML page without dynamic features.

- Status Code#

A status code is a three digit number returned by the server to indicate the result of a request, such as

200for success or404when a page doesn’t exist.- Protocol#

A protocol is a set of rules for how data is exchanged over a network, like HTTP, which defines how web clients and servers communicate.

- Resource#

A resource is any data or content (like a webpage, image, or file) that is available on a server and can be requested by a client.

- Request header field#

A request header field is extra information sent by the client to the server, such as the type of browser being used or the desired content type.